History often celebrates kings, queens, and wars. Such narratives obscure a quieter force: maritime trade. In the 6th–2nd century BC and 11th–15th century AD, Mediterranean ports, not battlefields, fueled economic and cultural prosperity, laying the foundations for the Roman Empire and Renaissance Europe. Two examples—Carthage’s trade empire and Venice’s commerce with Alexandria—reveal how merchants, not monarchs, shaped the Mediterranean’s golden ages. Yet, political ambition and intolerance often threatened this wealth, a lesson that resonates today.

Carthage’s Maritime Empire (6th–2nd Century BC)

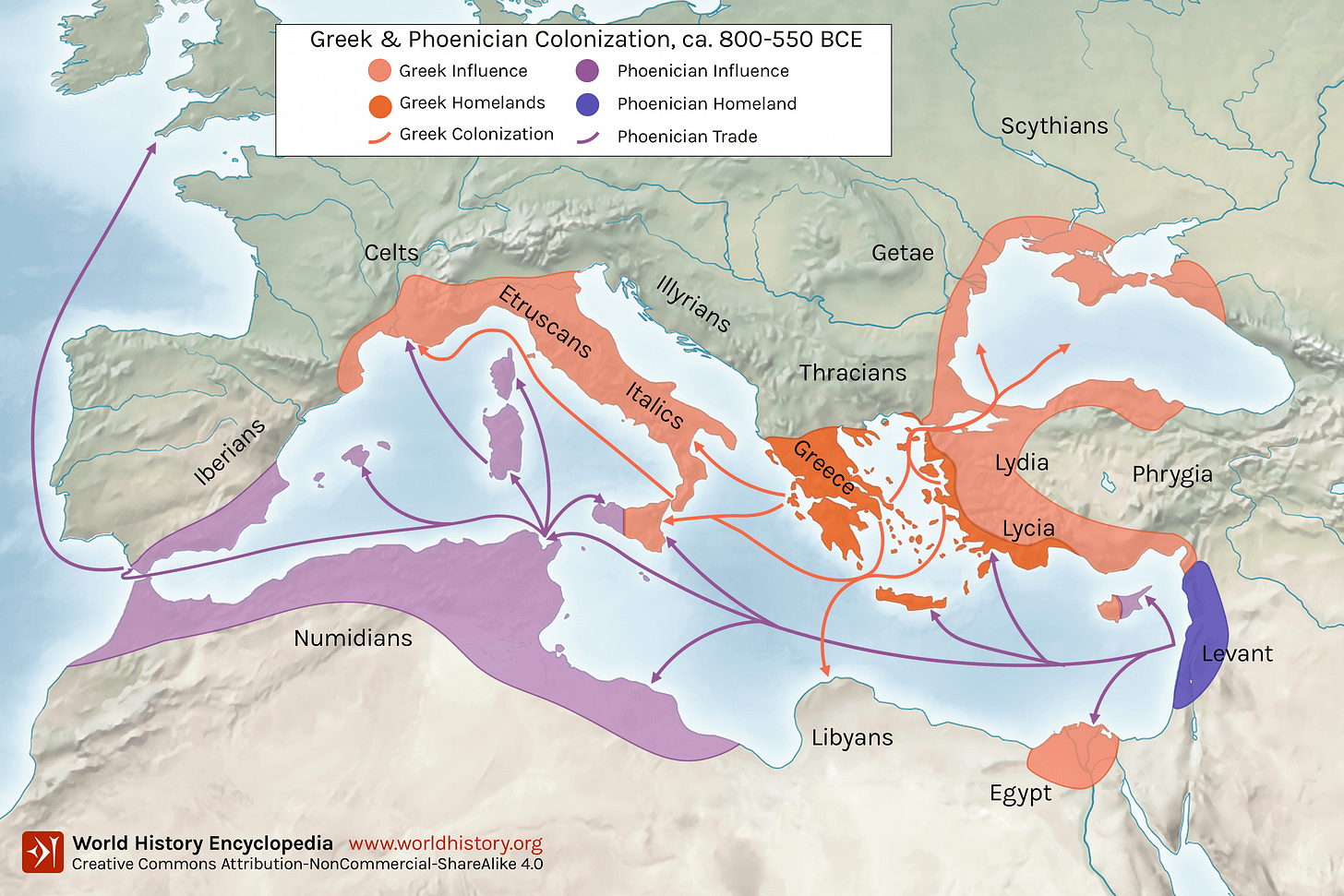

In the 7th century BC, when Assyrian conquests extinguished Phoenician cities, Carthage, a North African colony, rose to prominence. Under the Magonid dynasty from around 550 BC, it became the western Mediterranean’s commercial and military powerhouse, overseeing Phoenician (Punic) colonies in Sicily, Sardinia, and southern Iberia. Carthage founded some 20 new settlements in Iberia and bolstered agriculture in Sardinia and maritime infrastructure in Motya, Sicily.

The Power of Merchant Networks

Carthage thrived as a hub of diverse merchants—Punic and foreign—organising the trade of goods across regions. In Etruscan Caere, so many Punic traders settled that it was dubbed “Punicum.” Alexandria, after Alexander the Great’s conquest, emerged as the Mediterranean’s second-largest port, while Sicilian cities like Syracuse grew rich shipping grain to Greece. These networks fostered cooperation, despite political tensions.

Carthage’s 700-merchant-ship empire connected distant markets. It imported tin from Cornwall and silver from Iberia’s Gadir (modern Cadiz), becoming the western Mediterranean’s leading bronze producer. Its estates yielded olives, grain, and wine, while factories processed salted fish and sauces. Egyptian spices, African ivory, and European amber flowed through its markets. By 450 BC, every Carthaginian home had piped water and sewerage—a testament to trade’s ability to elevate living standards beyond the elite.

Political Ambition’s Cost

Yet, political rivalries disrupted this prosperity. Syracuse’s leaders, driven by ambition, expelled Punic merchants and attacked their settlements, culminating in the destruction of Motya in the 4th century BC. In 480 BC, Syracuse’s ruler Gelon defeated a Carthage-Himera alliance, and in 474 BC, he triumphed over the Etruscans at Cumae. These conflicts, fueled by racial and territorial disputes, strained trade networks. Syracuse’s hostility alienated even fellow Greeks, who favoured peace due to their reliance on Sicilian grain. Carthage, seeking stability, allied with Rome, paving the way for Rome’s dominance—and its extraordinary wealth, built on trade.

Despite these disruptions, Mediterranean commerce grew, proving trade’s resilience. Carthage’s story shows that merchants, not warriors, were the true architects of prosperity.

Venice and the Renaissance Trade Revival (11th–15th Century AD)

A millennium later, Mediterranean trade again drove progress, this time fueling the Renaissance. While histories emphasise Crusades, the Reconquista, and Byzantine decline, merchants quietly rebuilt wealth. Italian ports—first Amalfi, then Venice and Genoa—centered their trade on Alexandria, the Mediterranean’s richest hub.

Alexandria’s Merchant Hubs

In Egypt, unlike feudal Europe, Jewish merchants, some descended from Carthaginian exiles, traded freely. Fustat, near Cairo, became a nexus for Andalusia-India trade, handling spices, silk, foodstuffs and gold with Aden and Sicily important links in between. The Geniza documents reveal a cooperative network of Jewish, Muslim, Christian, and Hindu traders, ignoring Islamic laws that doubled duties for non-Muslims.

Venice leveraged Alexandria to amass wealth, trading spices, silk, and glass. By the 13th century, its merchants pooled capital and hedged risks, funding voyages to the Black Sea, Levant and North Africa. Genoa established merchant enclaves (funduqs) in Tunis and Bougie, partnering with local Muslims. Treaties between Italian, Catalan, and Tunisian states ensured equal protection for traders, and joint ship ownership was common. In Tyre, 400 Jewish glassmaking families, heirs to Phoenician craft, produced exquisite wares, some relocating to Venice under Crusader invitation.

Trade’s Cultural and Economic Legacy

This commercial boom transformed northern Italy. Venice’s Grand Canal gleamed with palazzos, and the Rialto Bridge, built in 1264, symbolised its wealth. By 1400, Venetian galleys, now three-masted and larger, carried pepper, ginger, and silk, while bulk ships hauled grain and timber. Trade enriched hinterlands as far as southern Germany, spurring manufacturing and population growth. Intellectual vigor followed: double-entry accounting emerged, merchant guides standardised weights and measures, and literature flourished with Dante and Boccaccio.

Yet, competition sparked conflict. Venetian-Genoese wars in the 14th century, the first commercial wars since antiquity, echoed earlier Greek-Punic clashes. Persecution also loomed: Sicily’s Jewish merchants faced expulsion by Catholic monarchs, and Venice restricted Jewish traders, though many persisted.

Decline’s Warning Signs

By the 15th century, threats emerged. The Ottoman conquest of Anatolia and southeast Europe from the 1450s disrupted trade routes. In Castile, tax-exempt nobility and anti-Semitic pogroms stifled commerce, while Egypt’s increasing state control choked its economy. Venice, shifting from a maritime to a bureaucratic state, imposed high taxes, draining its vitality. These shifts mirrored antiquity’s decline after 250 AD, when hostility to merchants weakened economies.

Lessons from the Mediterranean

From Carthage to Venice, maritime trade drove Mediterranean prosperity, creating wealth that wars and dynasties merely redistributed. Yet, political ambition—Syracuse’s aggression, Castile’s intolerance, Venice’s bureaucracy—repeatedly threatened this engine. Today, as global trade faces disruptions, the Mediterranean’s story reminds us: open ports and cooperative networks build prosperity; division and exclusion erode it.

For a deeper exploration, see How Maritime Trade and the Indian Subcontinent Shaped the World. IceAge to Mid-Eighth Century and The Millennium Maritime Trade Revolution, 700–1700: How Asia Lost Maritime Supremacy.

Leave a comment