Today’s commercial shipping networks are many and complex and have evolved over centuries. In the last 50 years they have exploded in volume and extent, shifting eastwards at considerable pace. But what was the world’s first sustained shipping network?

Economic Powerhouse of the Ancient World

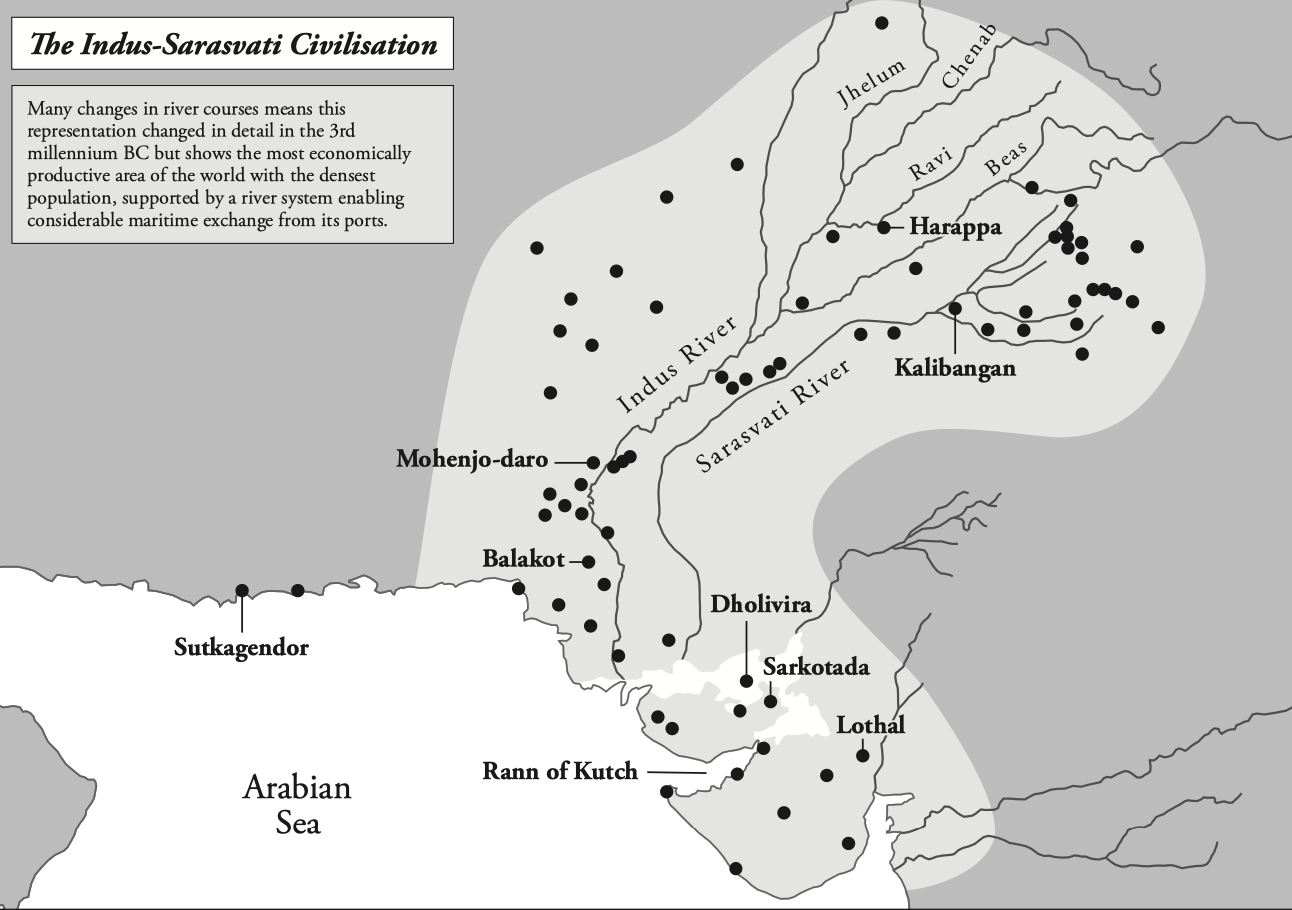

It was undoubtedly the one emanating from northwest India’s Indus-Sarasvati civilisation, the world’s most economically productive area from well before 3500 BC. Lothal seems to have been its most important port after Dvarka was drowned in the 5600 BC worldwide Flood. Its harbour could accommodate up to 30 ships each carrying 60 tons. Other ports included Dholavira, Rangpur, Bhagatrav, Sutkagenda, Balakor and Kuntasi.

About 500 sites in Kutch alone indicate concentrated activity radiating from ports. Seals, which identify ownership of goods in transit, also demonstrates the vibrant, dynamic mature network. Ships depicted on jars, seals and clay models conform with those described in the Rig Veda.

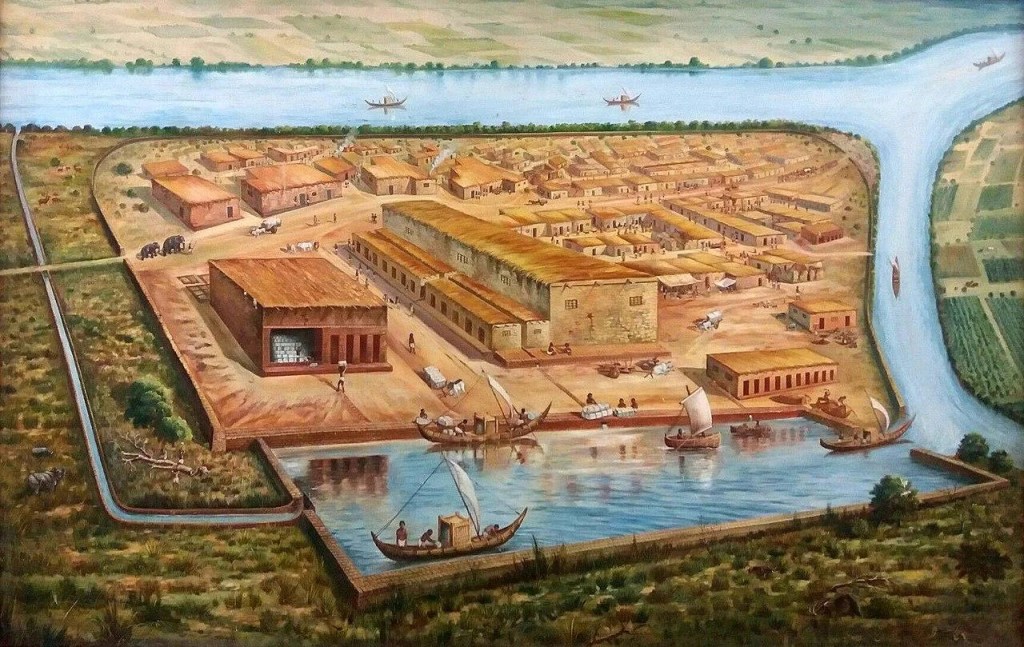

Dockyards, warehouses protective walls, irrigation canals and granaries, signs of community and merchant endeavour, contrast with Egyptian and Mesopotamian archaeological excavations; lavish temples, tombs and palaces rather than civic amenities, reflecting perhaps Indian kings’ sense of duty as reflected in the Arthashastra.

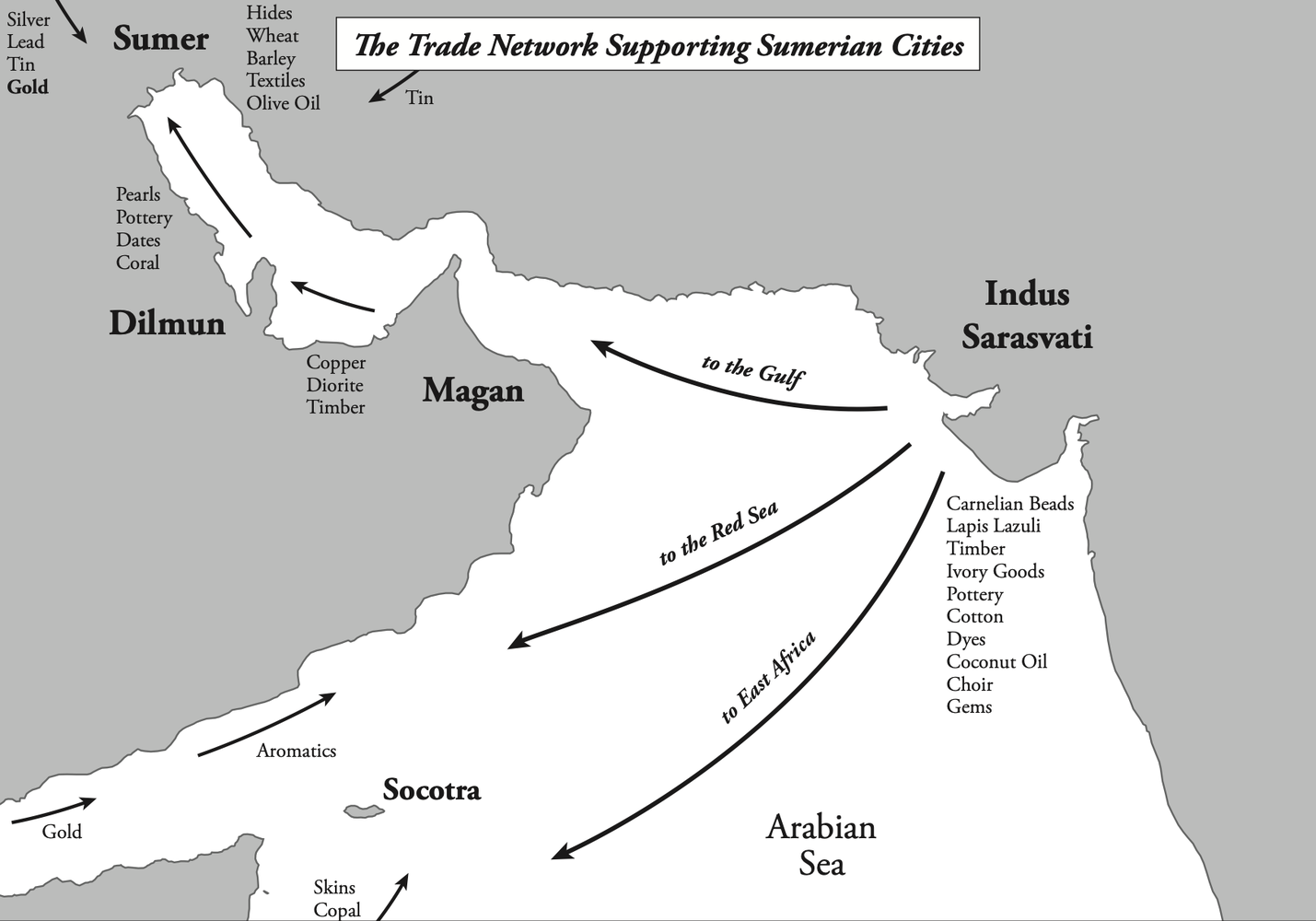

Valuable Indian Exports to Sumer

The area was ideally suited to supply the arid and largely timber-free Sumerian cities of Eridu, Ur, Uruk, Assur and Lagash with rice, fruits, spices, pulses, ghee, cotton textiles, gems, pepper, timber, sandalwood, tortoiseshell and its manufactured shell, agate and carnelian beads produced on an industrial scale.

What were the exports of arid Sumer?

What could Sumer supply in return? It had few products the vast Indus-Sarasvati area needed. The answer, apart from woollen cloth made from the millions of sheep and goats and local coral and dates seems to be found in the activities of Sumerian merchants in northern Mesopotamia, Anatolia and the Levant, where it sourced copper, tin and especially silver and gold in return for its woollen textiles. India has always valued precious metals and the copper and tin was first made into bronze, probably in the Indus Sarasvati area which enabled it to accelerate economically after about 3000 BC.

The merchants and seafarers

Who were the merchants and seafarers? Mainly Indians! Evidence of their presence in Mesopotamia consists of their merchant seals. Overwhelmingly conclusive, no Mesopotamian seals have been found in India. Supplementing this, pictures of merchants in a particular style of hat are frequent in India but the same has been found in only one in Mesopotamia. Bloodstones from Dholavira have also been found in Sumer and its craftsmen used Indus-Sarasvati techniques for boring beads.

Inter-Gulf merchants and seafarers were mainly from Magan (Oman) and Dilmun (Bahrain). Ancient texts refer to shipwrights of Magan, which unlike today was thickly forested. They did get to northwest India but the majority it seems were Indian. Vedic texts are suffused with passages about seafaring merchants sailing from India to Sumer, east Africa, Egypt, the Maldives, Java and Sumatra. The Rig Veda mentions ‘merchants who crowd the great waters with ships’ and credits Varuna, god of the sea, with navigating knowledge, similar to Polynesian techniques of studying the direction of bird flights. Three-masted and 100-oared ships are mentioned with trade explicitly undertaken ‘for our profit, pour forth seas filled with a thousand-fold riches.’ Moreover, much Rig Veda imagery is maritime.

The Gold Hypothesis

But were Sumer’s re-exported metals enough to sustain their imports? They must have needed to source more gold. I suggest that the origin of Uruk’s invasion of Egypt to create Pharaonic Egypt, traditionally dated to 3000 BC (but I think nearer 2750 BC) was for more control of gold supply for this very purpose. Controversial? Yes, but the beauty of studying maritime trade is you can look at the big picture. Specialists of Egypt, Mesopotamia and India are supremely valuable in uncovering the details, but they can miss the bigger picture and wide impact that maritime trade can highlight.

Further details can be found in How Maritime Trade and the Indian Subcontinent Shaped the World.

Leave a comment