Why its Correction Matters to Historians of all Areas.

Everyone has heard of the post-Roman empire Dark Age, fewer of the Mediterranean Bronze Age Dark Age. In 1991 Peter James and a team of specialists in ancient Mediterranean history encapsulated the growing doubts of many historians about the conventional chronology of the Mediterranean Bronze Age in their book Centuries of Darkness. This conventional timeline has a widespread collapse of civilisations following the Trojan War, fall of the Hittite Empire and political fragmentation of Egypt into various native and foreign mini-kingdoms, which Egyptologists term the Third Intermediate Period.

The ensuing Dark Age is said to have endured for 300 years, marked by a 60-90% population decline, the loss of writing and pottery-making skills, an absence of kings, trade or historical records. It resembled less a Dark Age than a veritable black hole and it echoed across the Mediterranean. Then, around 800 BC, societies seemingly reemerged as if by magic. The core issue is that Egyptologists, confident in their dating, largely avoided radiocarbon analysis – unlike in Northern Europe – and dismissed any discrepant results that did not fit their narrative.

By contrast, the Dark Age following the Roman Empire’s collapse, from about 400 to 750 AD, featured severe population decline and scarce sources, yet archaeological evidence, sources and records persist but unlike the magical Dark Age, maritime trade volumes took over a millennium to recover to mid-2nd-century levels. This alone should ring alarm bells.

This chronology matters more than for the Bronze Age Mediterranean. Much Middle Eastern dating depends on Egyptian dates and some Indian dates are predicated on that and some from radio-carbon dating. Thus it is often confused and confusing. So Indian historians should be interested and add their weight to revisionists.

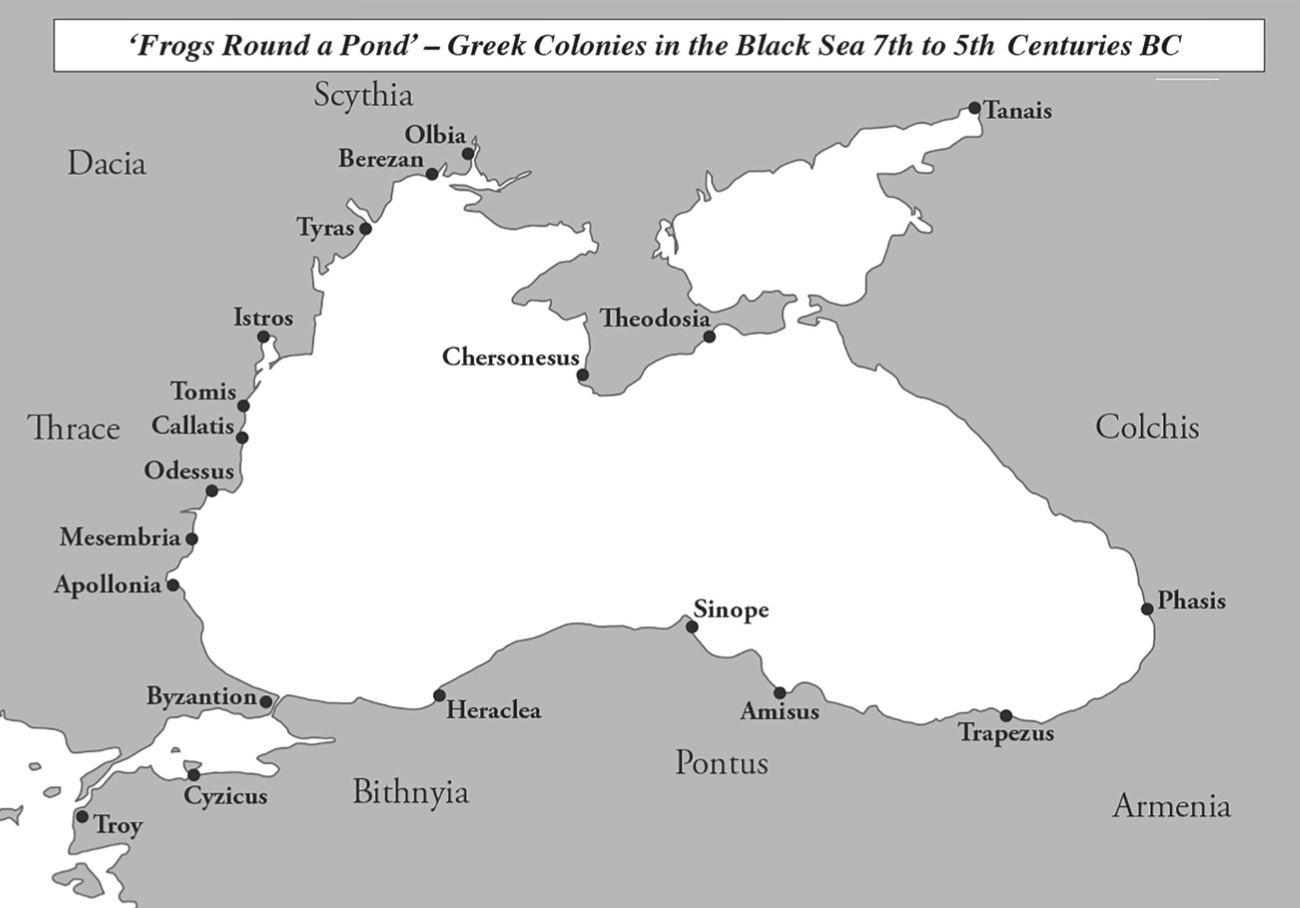

Back to the Mediterranean. Today, few scholars accept that quarrelling Greek kingdoms united to rescue or retrieve Helen. Homer crafted a compelling tale inspired by a real conflict, the last in a series of disputes with Troy, which obstructed access to vital Black Sea food sources amid a climate-induced drought in the eastern Mediterranean, with Greek states especially vulnerable.

But upon victory, the Greeks apparently delayed colonisation for 300 years before importing grain, fish, vegetables, fruits and exotic meats like pheasants from multiple Greek ports, likened to ‘frogs round a pond.’ This 300-year wait strains credulity. Great historian Fernand Braudel also puzzled over why the Tursha (who became the Etruscans) after migrating to Tuscany, waited 300 years to exploit its copper, tin and iron, which fuelled their success. Sir Alan Gardiner’s 1961 Egypt of the Pharaohs dedicated an entire chapter and extensive notes to these dating inconsistencies and was deeply sceptical.

A. R. Burn’s 1966 Pelican History of Greece argued that the Trojan War concluded not in the conventional 1180s BC but in the 9th century BC, using a 23.5-year generation length. Isaac Newton, in his lesser-known historical studies, proposed around 900 BC based on 18-year generations. Although starting points can vary outcomes, these generational estimates are far more plausible than 39 year generational lengths required to reach the 1180s BC.

What underpins Egyptologists’ unwavering confidence? First, the Dark Age conveniently bridges the Bronze-to-Iron Age transition. It begins in bronze and ends in iron. Second, as Robert Morkot has observed, they often view Egypt in isolation, embracing dates “more for familiarity than for fact,” and deem absolute chronology secondary since “for the New Kingdom…the relative sequence of kings is certain, so the absolute dates are less important.” An alarming conclusion!

Centuries of Darkness garnered positive reviews from most academics, some of whom cautioned against Egyptological resistance and advocated more radiocarbon dating. Regrettably, the warnings proved accurate and academia has largely retreated to familiar ground. Yet, dissent persists. Subsequent books and articles have built on the critique, which I summarised in How Maritime Trade and the Indian Subcontinent Shaped the World. A suggested reading list follows at the end.

Delving deeper into the Bronze-Iron Age conundrum, the biblical story of David and Goliath depicts Goliath’s armour: “He had a bronze helmet and wore a coat of scale armour of bronze… bronze greaves and a bronze javelin. His spear’s iron point weighed 600 shekels.” This portrays a Bronze Age warrior with nascent iron technology, fitting logically around 1000 BC. However, Tutankhamun, who is supposed to have died around 1323 BC was interred with two rust-resistant iron-bladed daggers, crafted with high nickel content; an advanced technique.

These daggers are attributed to Mitanni gifts. In 2014, a slag heap and ironworking site at Tell el-Hammeh in the Jordan Valley – Mitanni territory – was dated to about 1000 BC, though whether by radiocarbon or inferred from the Iron Age onset remains unclear. The Hittites also possessed ironworking knowledge. In 2003 archaeologists at Hyderabad University radiocarbon-dated ironworking in the Ganges Valley to as early as 2800 BC, artifacts from around 1800 BC and large-scale production by 1300 BC, but this has been ignored by Egyptologists. These dates align with post-Sarasvati River diaspora migrations including those of the Mitanni and Hittites to Mesopotamia and Anatolia.

Yet, this leaves insular Egyptologists perplexed by sophisticated iron blades in Tutankhamun’s tomb, predating expected timelines by 300 years, without considering flaws in their chronology. Suspicions of climate-driven Bronze Age collapse prompted reports in 2013 and 2014, yielding contradictory findings. Stronger evidence indicates decades of drought in the eastern Mediterranean, followed by abundant rainfall. This era’s climate disruptions, akin to those causing the First Intermediate Period a millennium earlier, warrant further exploration, this time in the correct centuries, which will surely identify these climate-induced crises.

Suggested Reading

Nick Collins – How Maritime Trade and the Indian Subcontinent Shaped the World (2021)

Peter James et al. – Centuries of Darkness (1991)

Peter James et al. – Mediterranean Chronology in Crisis (Studies in Sardinian Archaeology, 1995)

Peter James et al. – “Updating Centuries of Darkness” (British Archaeology, April 1996)

Rakesh Tewari – “Origins of Iron Working in India: New Evidence from the Central Ganga Plain and Eastern Vindhyas” (2003)

Robert Morkot – The Black Pharaohs (2000)

Fernand Braudel – The Mediterranean in the Ancient World (1998)

Sir Alan Gardiner – Egypt of the Pharaohs (1961)

A. R. Burn – The Pelican History of Greece (1966)

Nikos Kokkinos – “Ancient Chronology: Eratosthenes and the Dating of the Fall of Troy” (Ancient West and East 8, 2009)

Leave a comment