It strikes me that the Out-of-India thesis, which dismantles the Steppe-based Proto-Indo-European (PIE) model, parallels the outdated assumptions that still dominate debates on the origins of English.

The Few and the Many

In both the Aryan Invasion/Migration model and the standard “Anglo-Saxon origins” model, a small group supposedly arrives speaking an alien language which the larger native population then adopts wholesale for reasons never explained. In England’s case, the standard narrative is Anglo-Saxons displaced those speaking a Celtic language, Brythonic, of which there is not a shred of evidence.

These assumptions persist largely because English departments, particularly those invested in “Anglo-Saxon” studies, rely heavily on Beowulf as a foundational precursor of English. I have argued elsewhere that Beowulf is probably a Tudor forgery by out-of-work monks, well versed in crafting ‘documents’ to prove whatever anyone wanted who had enough money and will not revisit that here; instead, I focus on the origins of English itself.

No Invasion

The evidence does not support an Anglo-Saxon “invasion.” Some Germanic groups were already established in England along the Saxon Shore. When Roman legions withdrew in 410 CE, longstanding tribal rivalries resurfaced while Scots and Irish groups raided as far as southern England. Additional Germanic groups were invited as mercenaries from across the North Sea. Decades later, finding themselves militarily superior, they assumed kingship. All this is reported in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written in early forms of the imported Germanic ‘elite’ language. King Offa of Mercia, for example, explicitly states that his ancestors came from Anglin – now southern Denmark – formerly Frisian territory. But that does not imply this small group made all others change from what they were speaking, which was not a Celtic language.

The Chronicle around 1120 continues in recognisably English. The logical explanation is that, following the Norman takeover, specially trained Anglo-Saxon monks died out. Those wanting to continue it did so in their vernacular, English, varieties of which had always been spoken by the inhabitants.

English appears to descend from the Germanic dialects spoken by early migrants who moved into northwestern Europe. They were divided by the 5600 BC flood that formed the Channel. English was closely related to Frisian dialects which from Schleswig-Holsten to Bruges vary but there are common words: bûter (butter), rein (rain), boat (boat), brea (bread), grien (green) and tsiis (cheese). Medieval West Flemish from Bruges to Calais shows similar affinities: beuter (butter), hille (hill), dinne (thin), and so on.

Celts in Britain

Celtic influence in Britain was largely confined to the western fringe and arrived later than the Germanic presence. Yet the conventional narrative insists on a linguistic sequence – Brythonic to Latin to Anglo-Saxon to English – in just a few centuries. We are asked to believe that a Northumbrian monk around 660–680 wrote Nu scylun hergan hefaenricaes weard (“Now must we honour the guardian of heaven”), and that within roughly 600 years this became Chaucer’s Middle English – essentially today’s English if the spelling is adjusted to its modern form: “A sword and buckler bore he by his side.” Such a transformation in so short a span strains credulity.

This pattern will be familiar to proponents of the Out-of-India model. It illustrates how some academics become unwilling to ditch outdated theories, adjusting them slightly but refusing to abandon them even when evidence collapses their foundations. The problem extends far beyond the AIT. Many say AIT is colonial history. Maybe, but I think this is more about some (not all) academic intransigence, unwilling to change opinions on something they have taught all their career.

Romance Languages

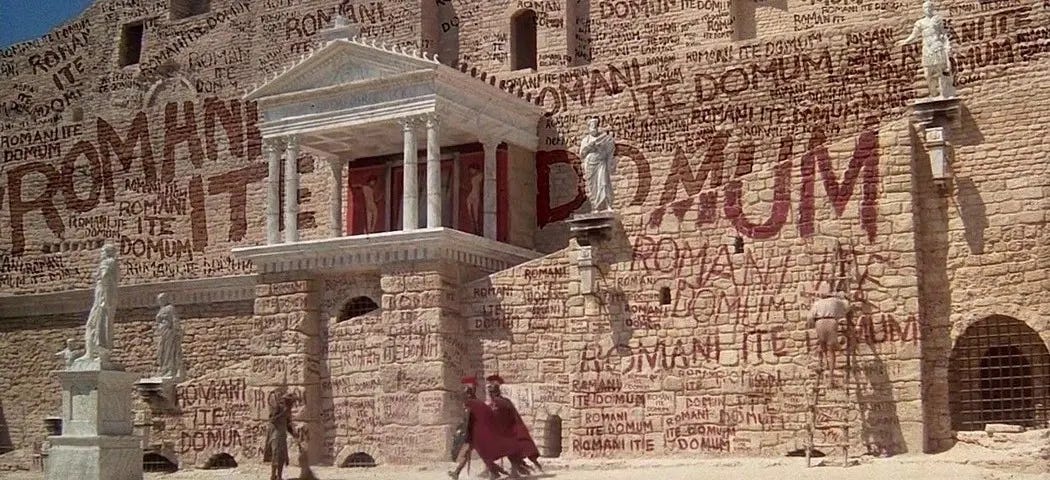

The common perception is that Latin was spoken by everyone in the Empire, imposed by Romans rather like John Cleese’s centurion in The Life of Brian, teaching a hapless peasant (Graham Chapman) the grammatically correct way of writing ‘Romans Go Home’ (Romani de domum- depending on word endings) and forcing him to write it 100-times as punishment for spelling it incorrectly in his initial graffiti. Then in the barbarian invasions, this broke down and evolved into various forms of French, Italian and Spanish. Really? Linguistic experts know that Romance languages have a common root with Celtic (Itallo-Celtic) but have done nothing to dispel the myth. So Julius Caesar’s Veni, Vidi, Vici – I came, I saw, I conquered) becomes je juis venu, j’ai vu, j’ai vaincu, although je in southern France’s Occitan languages is usually ej. Furthermore the first line of a 12th century poem in the Occitan spoken around Bordeaux at the time, ‘Dos cavalhis ai a me selha ben e gen’ (I have two pure bred horses for my saddle) sounds closer to Spanish!

These issues concerning the history of English and Romance languages are discussed and clarified in greater detail in my book, How Maritime Trade and the Indian Subcontinent Shaped the World – particularly pp. 296–307.

Leave a comment