The Danger of Anti-Trade Ideology Destroying Wealth, Prosperity, and Power

For over a millennium, the world’s greatest maritime trading system was not European but Asian. From China and Japan through Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent, dense networks of ports, merchants, shipbuilders, financiers and navigators generated unprecedented wealth, urbanisation, and cultural exchange. Yet between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries, this system fragmented and collapsed, not primarily through external conquest, but through a series of ideological, political, and institutional choices that systematically undermined trade itself. This article condenses the core argument of The Millennium Maritime Trade Revolution: that maritime supremacy is sustained by cultural attitudes to commerce and a willingness to remain adaptive. The lessons remain urgently relevant today.

Ming China and the retreat from maritime trade

The Chinese Ming dynasty’s pursuit of Confucian purity led to a catastrophic policy reversal: from 1372, foreign travel and maritime trade were banned and Chinese merchants and seafarers were criminalised. Centuries of development in the world’s finest porcelain and celadon, formerly exported with great profit, were halted. Potters relocated to Vietnam and Siam, where exports rose dramatically. Chinese merchants migrated to Palembang, Ayutthaya, Sukhothai, Malacca, Manila, Brunei and Phnom Penh – new Chinatowns. The great Song and Yuan trading fleets that dominated the Indian Ocean and South China Sea as far as Aden disappeared. In their place, merchants from Southeast Asian ports, Chinese émigrés and western Indian Ocean traders, especially Indians and Muslims, assumed control. One long-term consequence was the accelerating Islamisation of Southeast Asia.

The rise and limits of Indian maritime power

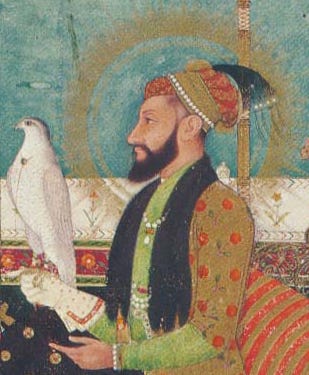

Indian ports correspondingly increased in importance. Calicut, Cochin, Cannanore and Quilon were semi-independent polities within the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire, which encompassed some 300 ports across India’s eastern and western coasts. Its inland capital’s rulers boasted that they were “lords of the eastern and western oceans.” Founded in 1336 to resist Islamic incursions from the north, Vijayanagara represented a rare Indian state with a serious maritime orientation. By contrast, the Delhi Sultanate and later the Mughal emperors showed little interest in ports or trade, financing their armies primarily through heavy taxation of peasants, policies detrimental to northern Indian ports and merchants. Mughal attitudes toward commerce were openly dismissive. Maritime traders were described as “silly worms clinging to logs… of no concern to the prestige of kings.” Nevertheless, the Indian Ocean and South China Sea remained the world’s richest maritime trading system. Vijayanagara was defeated in 1565, surviving in weakened form until 1646.

Portugal’s incursion into Indian Ocean trade

Portugal’s entry into the Indian Ocean dramatically increased royal revenues and rapidly transformed Lisbon into a major European city. The Portuguese initially sought pepper, cloves, nutmeg, and mace, reshaping Europe’s spice markets and hastening Venice’s decline. Over time, enterprising Portuguese traders circumvented royal monopolies and engaged in inter-regional Asian trade. Yet spices were only a fraction of total commerce: trade in rice, salt, cloth, pickled and dried fish, fragrant woods, and metals was far larger in volume.

Portugal’s greatest impact in the Indian Ocean may have been its stimulation of inter-Asian trade and the introduction of South American maize, chillies, peanuts and sweet potatoes contributed to population growth and rising demand across Asia. Spain, which controlled much of South America, likely transmitted some of these crops via the Acapulco–Manila galleon trade. Ironically, this trade was officially prohibited by Philip II and, due to the Ming ban, was largely conducted by Chinese merchants in Manila. China desperately needed silver but could not obtain it legally under its own restrictions.

Dutch monopoly and the fragmentation of Southeast Asian trade

Seventeenth-century Dutch influence in Southeast Asia, enforced through monopolistic practices, marginalised legitimate local traders. Many were driven into piracy or dispersed to other ports, increasingly under Muslim control, further fragmenting the region’s commercial networks.

Japan’s self-imposed isolation

Japan likewise withdrew from the world, allowing trade only with Chinese and Dutch merchants, and even then solely through tightly controlled enclaves at Nagasaki.

The last great Asian maritime empire

The final major Asian maritime power was vast and largely illegal, controlled by Fujianese shippers and merchants. Li Dan in the early seventeenth century, built a maritime empire trading across China, Southeast Asia, and Japan, where silver had been discovered. He became the richest man in Asia. His son, Nicholas Iquan and grandson succeeded him. In the West he was called Coxinga. As the Manchu conquered China, Coxinga’s fleets continued to dominate maritime trade. He professionalised the network into an integrated organisation of five companies, extending into inland commerce. Over 80% of the junks trading between Nagasaki and Southeast Asia belonged to his organisation. Others paid tolls. The network dominated trade in silk, ceramics, gold, copper, silver, sulphur and spices and in the 1650, its peak, is estimated to be five-times more profitable in the region than the Dutch East India Company.

The Manchu offered him control of coastal trade under imperial suzerainty. From his perspective, he already controlled the coast and commerce, Accepting the offer would have removed the need to fight the Manchu; an attractive commercial proposition. However, he valued autonomy. He believed he could roll back Manchu power. Advancing on Nanjing, he was decisively defeated in 1659. The Manchu retaliated with a scorched-earth policy, depopulating a 30-mile-wide coastal zone to deny him provisions. Coxinga withdrew to Taiwan, which rapidly became Asia’s most important entrepôt. His son Zheng Jing maintained maritime dominance and even concluded trade agreements with the expanding English East India Company. However, entanglement in anti-Manchu rebellions proved fatal. By 1683, Taiwan was incorporated into the Manchu Empire.

Mughal collapse and the rise of European legal-commercial systems

Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s reign, marked by religious intolerance, wars against Hindus, conflicts with his own sons and policies that caused tens of millions of deaths through warfare and famine, fatally weakened the empire. Although Surat remained a major port, political instability led many merchants to relocate to English East India Company-controlled Bombay. Geographically less advantageous, Bombay however, offered something new: English Common Law as the basis for contracts. Merchants no longer needed constant negotiation with Mughal officials for permissions, favours, hospitality and bribes. Bombay began to grow rapidly. By 1700, Asian merchants still controlled most Asian trade but a combination of anti-trade ideologies, Confucian isolationism, secessionism, continentalist Islam, and above all elite arrogance, steadily undermined that dominance. In football terms, these were own-goals.

Modern parallels

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Europe has exhibited a comparable pattern of maritime decline driven by abstract ideological commitments: socialism, protectionism, open borders, climate alarmism and again, above all, arrogance and an unwillingness to compromise or learn from others. By contrast, maritime values have been reborn in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Dubai and most recently India, which is now beginning to follow the same path.

Further details can be found in my book The Millennium Maritime trade Revolution: How Asia Lost Maritime Supremacy and for the modern period, The Ascent of Maritime Trade (forthcoming April 2026).

Leave a comment